One Person’s Honest Opinion is Another Person’s “Disinformation”…

and the Story of How Galileo Got Cancelled

One term you may see bandied about freely and indiscriminately is “disinformation.”

Its users see it as a label for calling out deceptive speech, oftentimes to discredit and sometimes to censor that speech. Critics see the increasing use of the term as a propagandist strategy used to marginalize anyone who might dissent from a general narrative.

As with any controversial term a good starting point for analysis is the dictionary.

Merriam-Webster defines “disinformation” as “false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.”

In other words, the dictionary says knowingly lying is disinformation. Fair enough. But what if someone is simply stating an opinion based on facts that others don’t accept? Does that constitute disinformation? Where are the boundaries? This is important.

If someone states an opinion that climate change isn’t a man-made crisis, that men really didn’t walk on the Moon, or that there was a second gunman in the JFK assassination, is that disinformation? Are conspiracy theories and disinformation one and the same? Or, even more to the point, are all conspiracy theories baseless?

And what about theories that may not be popular at first, but after no small amount of public debate, eventually prove to have certain merits?

The Galileo Galilei Case

Galileo Galilei, born in 1564, is widely regarded as the father of modern science and made major contributions to the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics and philosophy. Keep this in mind anytime you hear someone today say, “Trust the science.”

In the 1600s, there was no Internet mob or federal court system to determine what is and is not acceptable in society. Instead, there was the Catholic Church.

A man by the name of Nicholas Copernicus wrote a book called “De Revolutionibus,” which represented the first modern scientific case for a heliocentric (sun-centered) universe. In other words, the argument was that the earth revolved around the sun and not the other way around.

This was enough to earn a place on the Church’s index of banned books. A parallel today would be for Big Tech to ban the book from Amazon.

At the time, Pope Paul V called Galileo to Rome and made it clear to him he could no longer endorse Copernicus publicly. Again, using today’s climate for communications, that means no tweets, no blog posts, no YouTube videos, no selfies with his buddy Copernicus. Nothing. Galileo could provide no public endorsements of this banned way of seeing the universe.

So, what does Galileo do? Well, in 1632 he decides to publish his “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,” which doesn’t specifically endorse Copernicus’s view, but it gives it a fair hearing. That didn’t go over well in Rome with the ‘fact checkers’ who saw Galileo as deliberately spreading disinformation.

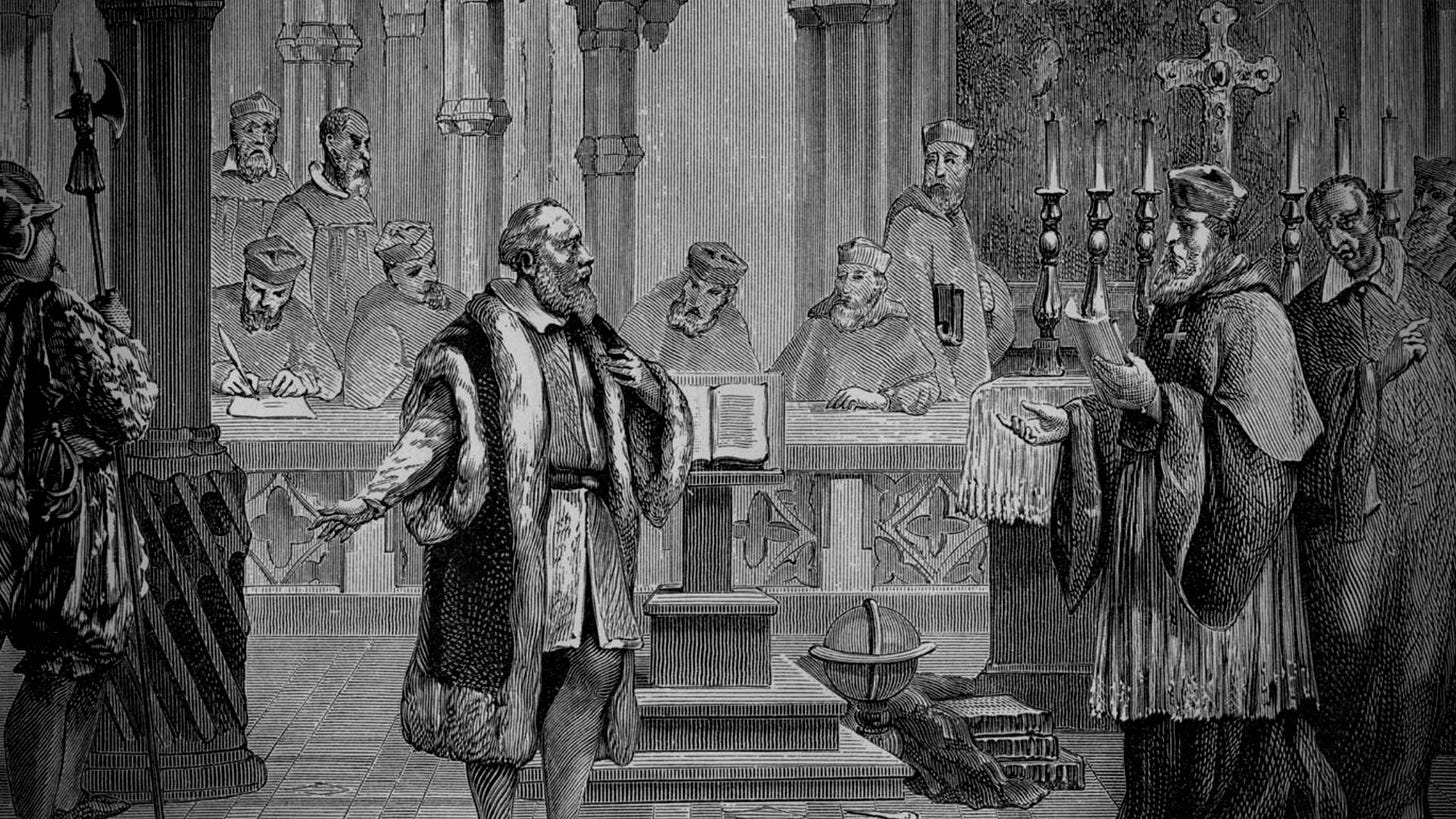

Galileo was called to stand before the Roman Inquisition in 1633. Today, this would be like being summoned to Seattle to stand before and be judged by the internet mob.

In the beginning, Galileo denied that he had advocated heliocentrism – that the earth revolved around the sun – but he later tried to explain that his actions were unintentional.

Not good enough for his inquisitors. He was convicted on grounds of “vehement suspicion of heresy.” He was threatened with torture and forced to bow down, express remorse and seek forgiveness. Again, in today’s terms, this means he was forced to apologize to the mob and still he was cancelled.

By the time Galileo was put on trial, he was almost 70 years old, and yet he would live another nine years under house arrest.

Fortunately for him and for the world, Galileo was able to use that time to write about his early motion experiments, which represented his last major scientific contribution to civilization.

If you can see some of parallels between that time and our own, what you are really seeing is that human nature hasn’t changed much. People with unpopular views are often persecuted even if they’re right. Sometimes especially if they’re right, because they’re seen as a threat to the accepted narrative, an agenda, or someone in power.

So, in that context, I ask you, should everyone who states an opinion that dissents from generally accepted assumptions be shut down and shut up through private and public censorship?

More questions. Should today’s tech platform “Trust and Safety” departments be, like the Church of the 1600s, the inquisitor and the judge for what is disinformation or not?

More Questions than Answers

My apologies if I’ve hit you with more questions than answers to this point, but the barrage of questions illustrates both the complexity of the issue and the problem with terms like “disinformation.” And they further illustrate the need for open and public debate, rather than the need to shut down debate.

“Disinformation” is not a precise word. It is completely subjective. It is vague and defined by the parties actively engaged in the debate, people who have something to gain by discrediting and censoring the other side.

Are People Permitted to have Opinions?

If there are 50 people in the room all witness to the same debate between two sides of an issue, chances are very good that you will get 50 distinct versions of what was disinformation and what was opinion. So, where does that leave us?

It brings us back to where we were as a society before words like “disinformation” entered the current vernacular and took control over what we can say and what we cannot.

The price for living in a free society is that speech is messy. Something we would have accepted as a difference of opinion not long ago, in the current environment is deemed a battle over “disinformation,” and for that reason alone, it should be banned from social media, banned from books, banned from the news and opinion media, banned from any public discourse. Perhaps the speaker should even be criminally prosecuted.

Case in point. A mild one at that. Is coffee good for your health or bad for your health? After we talk to a few doctors and look at the science it’s anyone’s guess…and by anyone’s guess, I mean anyone’s opinion.

Imagine if some doctors who said coffee is bad for you could post whatever they want on YouTube, but doctors who say coffee is good for you immediately have their YouTube videos taken down and their Twitter/X accounts suspended all in the name of “the common good” or the public’s health and well-being. Someone in power doesn’t want you to have access to coffee, and they don’t have to tell you why.

Accusations of “Disinformation” are Smear Tactics

At the end of the day, one person’s honest opinion – sometimes a highly informed opinion – is that person’s critic’s “disinformation.”

If you consider yourself fair-minded, permit me to make one recommendation.

Think twice before you label something “disinformation” or “misinformation.” Because when you do, you are smearing the messenger. Chances are, you are labeling an opinion a lie, and accusing the speaker of being a liar. Not very civil, is it?

If you value your own right to freedom of expression, you must honor the next person’s right to the same, no matter how vile or uninformed you think that person may be. Because if you don’t, and enough people join with you on the notion that freedom of speech is a selective privilege only to be given to a few by a few – and not an equal right for all – a dark day is ahead for you, too. Dark days are ahead for all of us, especially those who work in communications, and we’d owe those dire consequences to anyone who would favor public or private censorship today.

It’s time to ratchet down the vitriol.

“Disinformation” is in itself an intentionally imprecise word. It’s propagandist by nature. It’s an uncivil accusation that compounds problems already associated with lack of civility. Perhaps most deviously, it’s a blunt, merciless tool used to deny others freedom of expression as a justification for censorship in all of its forms.

When you consider use of such a word, you are making a choice to whether you will be divisive or unifying. Whether you will be oppressive or fair. By simply stepping back and using a more reasonable and equitable word, you can take the higher road.